Resilience Determinations

Resilience Determinations

Resilience is defined as the ratio of energy given up in recovery from deformation to the energy required to produce the deformation, usually expressed as a percentage. Hysteresis is the percentage of energy loss per cycle of deformation of 100% minus the resilience percentage. Hysteresis, the result of internal friction, is the conversion of mechanical energy into heat. Heat build-up is measured as the temperature rise resulting from hysteresis.

In general, resilience is determined in one of four ways: from a low-speed stress-strain loop; by an impact test; by free vibration; or by forced vibration methods.

Low-speed stress-strain is obtained by loading and unloading a specimen in tension, compression, or shear, using a low rate of strain and large deformation. Since most practical applications involve vibratory stresses of relatively high frequency and low amplitude, the low-speed stress-strain loop is not often used for measuring hysteresis.

The most widely-used methods for measuring resilience by impact involve rebound in some form. A very simple test consists of dropping a metal ball from a known height onto a firmly supported rubber specimen and then measuring the height of rebound, as with the Bashore Resiliometer. (FIG 1)

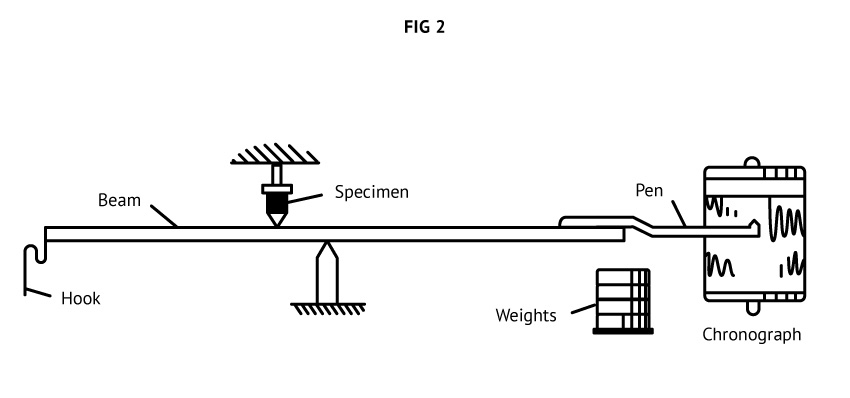

An impact test, however, is not equal to a vibration test, because there is no cyclic interchange of potential and kinetic energy. A widely-used instrument that measures vibratory resilience is the Yerzley Oscillograph. (FIG 2) This instrument is popular due to its relatively high-speed deformation—many times faster than in a stress-strain loop, although considerably slower than with impact resilience tests—through one or more complete vibration cycles. Oscillographs are also favored because they yield precise and reproducible data. Nevertheless, the utilized frequency is not of the same order of magnitude as that of many applications involving vibration.

Yerzley Oscillograph

Damped-Free Vibratory Motion

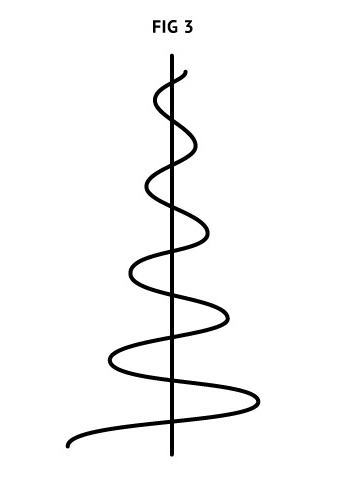

The apparatus consists of a balanced beam supported on a fulcrum. Weight is added to one end of the beam, thus straining the specimen on the opposite end of the beam. When the weight is released, a trace of the damping curve is physically recorded on a chart. Because the chart is mounted on a revolving drum, the trace has the form of a sine wave as shown in Figure 3. No significant test values can be obtained on materials that have a moduli greater than 280psi in compression with 10% deformation. Yerzley tests are therefore limited to urethane and rubber (durometer 90A or below).

The Bashore rebound test can be used on rubber of all hardnesses, but it does not yield results that are precise and distinguishing, as achieved with Yerzley resilience tests. Impact may cause a rise in temperature, resulting from heat generated within the specimen. Resilience is a function of temperature and usually increases when rubber is heated.

Forced vibration methods may be used to measure resilience, but they are usually employed to determine heat build-up in the specimen. The three flexometers described in ASTM D-223 are most commonly used for this measurement; they are known as the Goodyear, Firestone, and St. Joe flexometers. These devices are most frequently used to compare various compositions with one whose performance has been determined by actual use.

There is a tendency to assume that a composition having high hysteresis will be unsatisfactory for almost any use. This is not necessarily true. In certain vibration damping applications, compounds having relatively low resilience may be desirable, because their damping effect limits the maximum amplitude that may develop when in service.

For vibration damping purposes, resilience requirements are determined largely by the frequency and amplitude of vibration. Hysteresis in a low-resilience compound would cause excessive heat build-up in the part. In this case, a highly-resilient composition should be used.

Damping refers to the reduction of vibration amplitude in a free vibration system. Damping is a result of hysteresis, and the two terms are often used interchangeably.

For a sample under forced vibration at non-resonance, heat generation, as measured by the temperature rise or by the equilibrium temperature, is more nearly related to the requirements of actual service than is resilience. The temperature rise at a given amplitude depends upon both the resilience and the compression/deflection of the rubber compound. The resilience determines the proportion of the vibrational energy that is converted into heat, but the actual value of the vibrational energy at a given amplitude is proportional to the dynamic modulus.

Effect of Amplitude and of Frequency on Vibration Properties

If there is no appreciable rise in the temperature of the rubber, the dynamic modulus and dynamic resilience are independent of frequency, for the ordinary range of mechanical frequencies. Any rise in temperature of the rubber, due to internal heat generation from increase of frequency, tends to lower the dynamic modulus and raise the resilience. The dynamic properties of gum compounds are usually not affected by amplitude; but with filled compounds, the dynamic modulus decreases with the increase in amplitude, even if the temperature in the rubber is constant. Any rise in temperature contributes to this effect. Resilience is not affected by the amplitude except indirectly by temperature changes.

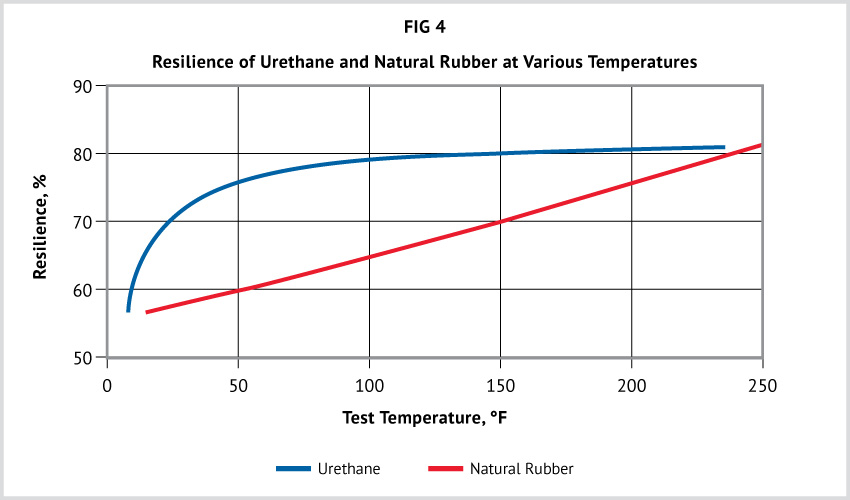

The resilience of urethane and natural rubber of 60 durometer A hardness, over the temperature range of 0°-250°F (-18°C-121°C), are compared in Figure 4.

The reliance of urethane increases as temperature is increased from 0° to 50°F (-8°C to 10°C), and then becomes almost constant. Being almost constant permits more confidence for designs in which service temperature may vary considerably.

The reliance of urethane increases as temperature is increased from 0° to 50°F (-8°C to 10°C), and then becomes almost constant. Being almost constant permits more confidence for designs in which service temperature may vary considerably.

Heat build-up in urethane parts, under high-frequency flexing, exceeds that of conventional elastomers and is the usual cause of premature failure under dynamic conditions. Because of the low thermal conductivity of urethane elastomers, heat developed by internal friction cannot readily be dissipated. The effect of heat build-up is, therefore, a very important consideration when designing with urethanes. Its adverse effects can be minimized by using thin cross-sections, from which heat is more easily dissipated. The high strength and load-bearing capacity of urethane elastomers makes possible such use of sections, which are thin enough to dissipate heat at the same rate at which it is developed.

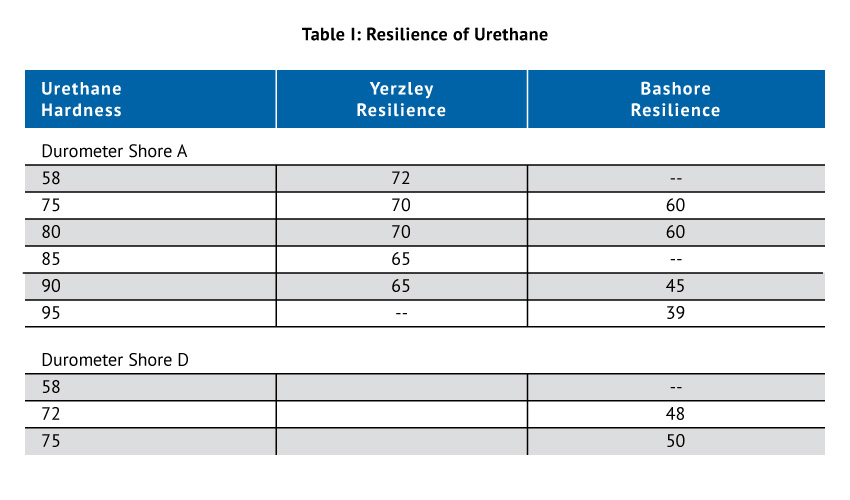

Values of resilience for typical compounds of urethane are shown in Table I.

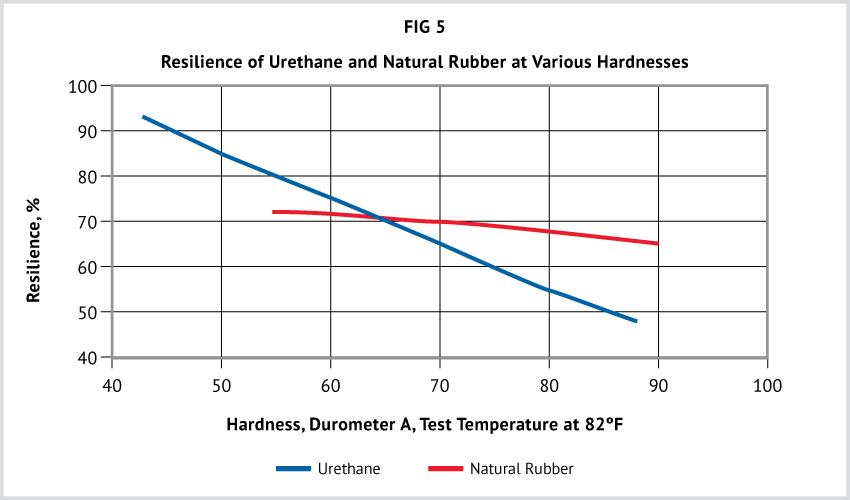

Compared to natural rubber, over a hardness range of 55A to 85A (figure 5), urethane shows little change in resilience.

Compared to natural rubber, over a hardness range of 55A to 85A (figure 5), urethane shows little change in resilience.

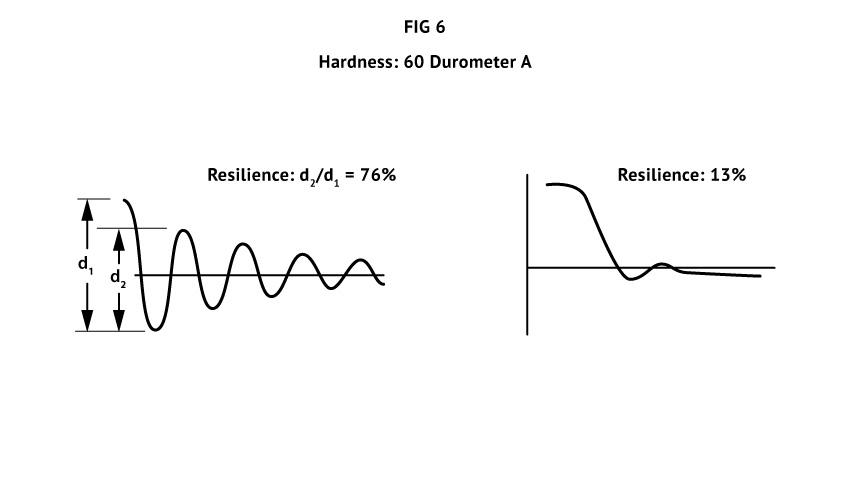

Urethane can be formulated to exhibit high or low resilience; the Yerzley Oscillograms in Figure 6 demonstrate these options.

Urethane can be formulated to exhibit high or low resilience; the Yerzley Oscillograms in Figure 6 demonstrate these options.

Urethane provides a greater hardness range with less sacrifice in resilience than is provided by many other types of elastomers. This is a characteristic of urethanes because they are non-reinforced, while rubber requires the use of fillers to develop optimum properties.

Urethane provides a greater hardness range with less sacrifice in resilience than is provided by many other types of elastomers. This is a characteristic of urethanes because they are non-reinforced, while rubber requires the use of fillers to develop optimum properties.

Access more articles in our Rubber Knowledge Center and our Urethane Knowledge Center.