Creep

When subjected to load, all elastomers exhibit an increasing deformation with time, known as creep. This occurs at any stress level and takes place in compression, tension, and shear loadings. In service, creep can be minimized by using low working stresses and by avoiding high temperatures. No rapid method has been developed for its measurement, because there is no known way of accelerating time effects without introducing inaccuracies in predicting rate of creep.

Creep is usually expressed in percent of deformation after the part is loaded, rather than in the unloaded dimension. Determination of creep takes place after an arbitrary short time interval—such as one minute, five minutes, or even one day—has passed since applying the load. Creep, expressed as a percent, equals total deformation minus initial deformation divided by initial deformation, times 100. When stress is removed, the part will attempt to return to its original dimension; however, it will never fully recover. The unrecoverable portion is called permanent set. Loads which allow intermittent recovery will exhibit less creep than if continuously loaded. However, continuous vibratory loading will increase creep, due to the generation of internal heat.

Strain relaxation is important in applications such as engine mountings, as it influences the alignment of various parts of the equipment. Yet, it is difficult to predict these properties for a given application without resorting to simulated service tests because several factors have important effects on them. Chief among these influences are amount of strain and operating temperature, as well as changes in these two aspects as a result of vibration.

The relative effects of variables have not yet been correlated such that the results of tests under one set of conditions will permit accurate prediction of creep under another set of conditions. But it has been established that the higher the initial strain, the higher the creep; also, the higher the temperature, the higher the creep. In general, the degree of creep is dependent on the type of strain. Creep is greater under tension strain than under equal compression strain. Creep is also more increased under dynamic loading than under static loading.

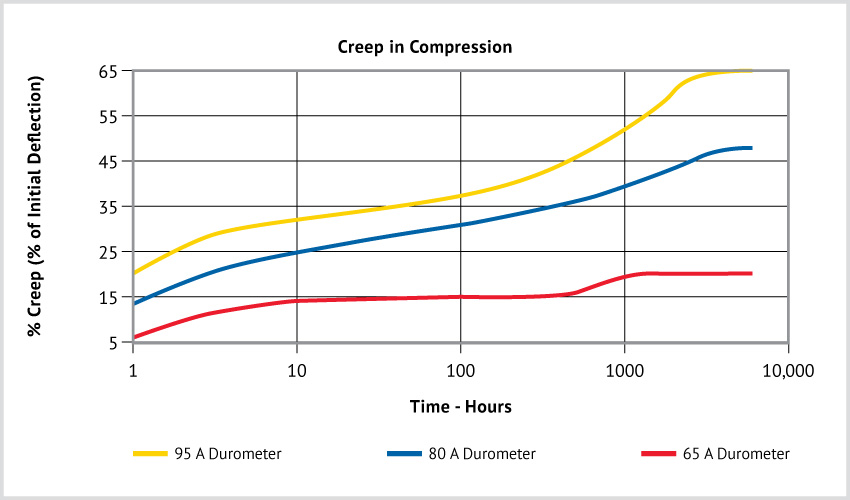

The creep characteristics of two urethane polymers, over a 10-month period, are shown on Figure 1. After approximately 3000 hours (18 weeks), creep reaches a plateau and becomes almost constant. The amount of creep is a function of stress level. This example involves a stress of 400 psi. Creep will continue at a very low rate after this point, which is the classic behavior of elastomers.

Figure 1

The actual creep of the 95durometer A compound was 0.033 inches after 10 months, compared with an initial deflection of 0.200 for a sample 0.500 inches thick. After the initial loading, creep is only 6.6%.

The creep rate of rubber materials of all kinds increases at elevated temperatures. Where dimensions are important, operating temperatures must be kept below 150°F (66°C).

Stress Relaxation

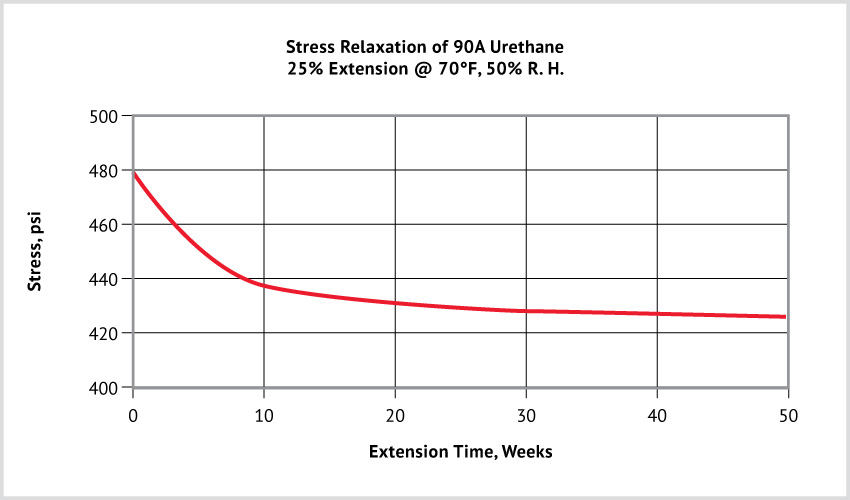

Stress relaxation is a decrease in stress when a polymer is held at a constant strain over a period of time. It is usually expressed in terms of percent stress remaining after an arbitrary length of time at a given temperature.

There is no standard method for determining stress relaxation. However, many laboratories have developed relaxation cells. These cells utilize the compression set specimen, and the test procedure parallels ASTM D-395 Method B. Stress relaxation for 50A urethane is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Access more articles in our Rubber Knowledge Center and our Urethane Knowledge Center.